How sleep works (and why it’s SO vital for health!)

Did you know sleep is absolutely essential to wellbeing – yet its an area people often struggle with – or totally overlook!

It’s also a big topic, so we’ve broken it down into two articles – this first one explains how sleep works, the second one has our top tips for a good night’s sleep!! It’s a great idea to read them both if you can, as this helps explain how sleep works, then gives you some great tips for a better night’s sleep ❤️

Lack of sleep has a major impact on our health and wellbeing – from day to day behaviors and the choices we make, to the risk of long term health issues and even our life expectancy….Over recent decades we are working longer, leading busier lives, and as a result sleeping less – and sleep deprivation is becoming increasingly common. Around 37% of young adults and 25% of working aged adults are chronically sleep deprived, these numbers have doubled since 1960, and continue to rise.

When we don’t get enough sleep, it increases the risk of many health issues, including type 2 diabetes (by up to 3x), dementia, heart disease, cancer and even allergies! Lack of sleep also affects our immune system, making you up to 3 times more likely to catch a cold 😨 Plus it increases our stress levels and stress hormones, making it harder to cope with day to day life (and also making it even harder to sleep).

Yet on the flip side, getting your zzzs helps with concentration, decision making, energy, mood, and even maintaining a healthy weight. It also affects our blood sugar levels and has a huge impact on our appetite – making us less likely to have food cravings and overeat, and more likely to make healthy food choices!!

We NEED around 7-9 hours of sleep each night for good health!

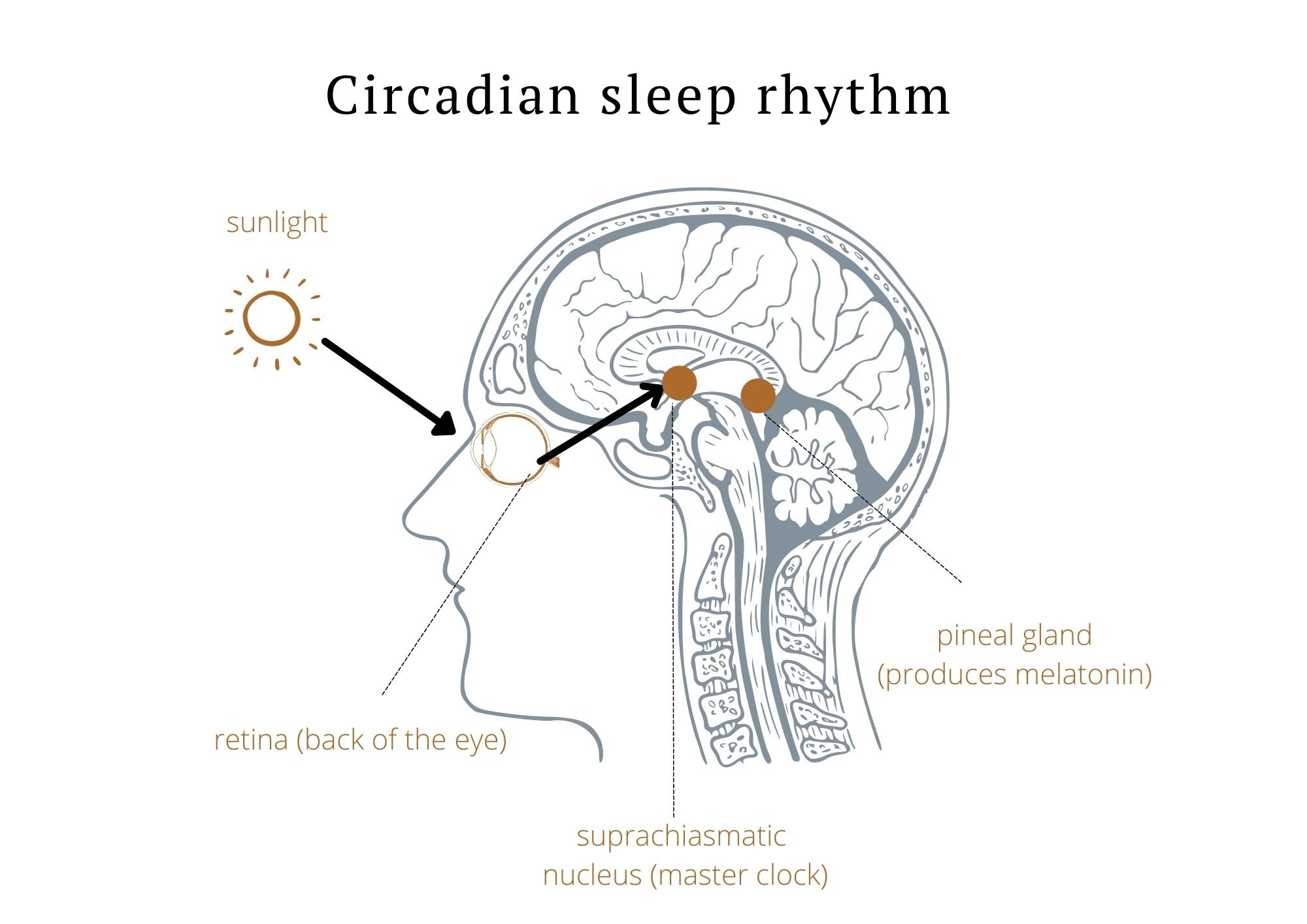

Getting less than 6 hours consistently has a big impact on our health as we just mentioned. Very few people can thrive long term on less than this – surviving is not the same as thriving 😉 Our sleep and body clock are regulated via a part of our brain called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) – this responds to various environmental cues, in particular blue light exposure, to tell our brain and body when and how long to sleep for, and when to stay awake.

It stimulates the production of melatonin from another part of our brain (our pineal gland) – melatonin is also known as our ‘sleep hormone’ as it is released at night from the onset of darkness and makes us sleepy. Its worth mentioning that low light levels increase melatonin – this is why bright lights at night, in particular screens, can mess with our sleep so much 😳.

Humans have lived in sync with nature for most of our existence – going to bed as it gets dark, and waking up with the sun. Modern life and artificial lights, as well as a lack of time outdoors in natural light, is a big part of why so many people struggle with sleep – we literally rely on light to be able to sleep well!!

Our SCN is also what sets our ‘body clock’, an inbuilt 24h clock that exists in virtually every cell in our body. Things like daylight, artificial light, and even a change in seasons can affect our body clock – as can stress, exercise, and what we eat. Our circadian rhythm is a key part of why having regular meal times, bed times, and periods of overnight fasting (time restricted eating) can be so helpful for our wellbeing.

Its also important to make a note of cortisol, as it’s the hormone we produce when we’re under stress, and can have a significant impact on our sleep. Cortisol and melatonin normally follow opposite patterns, with one going up as the other drops – cortisol starts to drop in the evening as melatonin rises, stays low overnight (lowest at around midnight), and rises again when it’s time to get up, peaking about an hour after we wake. Melatonin does the opposite. Interestingly, melatonin suppresses ‘stress hormone’ production, meaning a better nights sleep has a physical effect on our stress levels!

Chronic stress impacts on this hormone balance. Our body naturally produces cortisol (stress hormone) throughout the day, with levels spiking immediately after we wake up and gradually decreasing throughout the day. Cortisol also spikes when we are under physical or mental stress. When we have a stressful day, these extra cortisol spikes are the reason why you often feel hyper-alert during stressful situations, but can “crash” once the stress subsides.

Being highly stressed also affects our sleep, creating more night time wakenings and poorer quality sleep. And lack of sleep also increases our stress hormones (cortisol and adrenaline/noradrenaline), creating a vicious cycle …. This is why addressing stress is SO vital for a good night’s sleep!

Fortunately there are lots of effective evidence based ways to get a better sleep, most of which are completely free – so read on for part 2 if you’d like to know more!!

REFERENCES:

Hirshkowitz, M., Whiton, K., Albert, S. M., Alessi, C., Bruni, O., DonCarlos, L., Hazen, N., Herman, J., Katz, E. S., Kheirandish-Gozal, L., Neubauer, D. N., O’Donnell, A. E., Ohayon, M., Peever, J., Rawding, R., Sachdeva, R. C., Setters, B., Vitiello, M. V., Ware, J. C., & Adams Hillard, P. J. (2015). National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep health, 1(1), 40–43.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.010

Consensus Conference Panel, Watson, N. F., Badr, M. S., Belenky, G., Bliwise, D. L., Buxton, O. M., Buysse, D., Dinges, D. F., Gangwisch, J., Grandner, M. A., Kushida, C., Malhotra, R. K., Martin, J. L., Patel, S. R., Quan, S. F., Tasali, E., Non-Participating Observers, Twery, M., Croft, J. B., Maher, E., … Heald, J. L. (2015). Recommended Amount of Sleep for a Healthy Adult: A Joint Consensus Statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 11(6), 591–592.https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.4758

Charlot, A., Hutt, F., Sabatier, E., & Zoll, J. (2021). Beneficial effects of early time-restricted feeding on metabolic diseases: Importance of aligning food habits with the circadian clock. Nutrients, 13(5), 1405.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33921979/

Adafer, R., Messaadi, W., Meddahi, M., Patey, A., Haderbache, A., Bayen, S., & Messaadi, N. (2020). Food timing, circadian rhythm and chrononutrition: A systematic review of time-restricted eating’s effects on human health. Nutrients, 12(12), 3770.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33302500/

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. (2020, April 1). Circadian rhythms and circadian clock. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved on March 7, 2022, fromhttps://www.cdc.gov/niosh/emres/longhourstraining/clock.html

Manoogian, E., & Panda, S. (2017). Circadian rhythms, time-restricted feeding, and healthy aging. Ageing research reviews, 39, 59–67.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28017879/

https://www.sleepfoundation.org/sleep-deprivation

Sheehan, C. M., Frochen, S. E., Walsemann, K. M., & Ailshire, J. A. (2019). Are U.S. adults reporting less sleep?: Findings from sleep duration trends in the National Health Interview Survey, 2004-2017. Sleep, 42(2), zsy221.https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsy221

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). (n.d.). Sleep Deprivation and Deficiency. Retrieved October 20, 2020, fromhttps://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/sleep-deprivation-and-deficiency

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). (2019, August 13). Brain Basics: Understanding Sleep. Retrieved October 19, 2020, fromhttps://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/patient-caregiver-education/understanding-sleep

Grandner, M. A., Alfonso-Miller, P., Fernandez-Mendoza, J., Shetty, S., Shenoy, S., & Combs, D. (2016). Sleep: important considerations for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Current opinion in cardiology, 31(5), 551–565.

https://doi.org/10.1097/HCO.0000000000000324

Spiegel, K., Tasali, E., Leproult, R., & Van Cauter, E. (2009). Effects of poor and short sleep on glucose metabolism and obesity risk. Nature reviews. Endocrinology, 5(5), 253–261https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2009.23

Greer, S. M., Goldstein, A. N., & Walker, M. P. (2013). The impact of sleep deprivation on food desire in the human brain. Nature communications, 4, 2259.https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3259

Besedovsky, L., Lange, T., & Born, J. (2012). Sleep and immune function. Pflugers Archiv : European journal of physiology, 463(1), 121–137.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00424-011-1044-0

Kim, T. W., Jeong, J. H., & Hong, S. C. (2015). The impact of sleep and circadian disturbance on hormones and metabolism. International journal of endocrinology, 2015, 591729.https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/591729

Cappuccio, F. P., D’Elia, L., Strazzullo, P., & Miller, M. A. (2010). Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep, 33(5), 585–592.https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/33.5.585

https://www.healthline.com/health/cortisol-and-sleep

Theresa M. Buckley, Alan F. Schatzberg.On the Interactions of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis and Sleep: Normal HPA Axis Activity and Circadian Rhythm, Exemplary Sleep Disorders .The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 90, Issue 5, 1 May 2005, Pages 3106–3114, https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2004-1056

Han, K. S., Kim, L., & Shim, I. (2012). Stress and Sleep Disorder. Experimental Neurobiology, 21(4), 141–150. Retrieved fromhttps://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3538178/